As musicians, we practice being as “in the moment” as possible. We are vessels for the music we perform. Like how we can change the sounds of our instrument to embody the emotions, so too must our bodies follow with the flow. Manufacturing emotions creates physical tension and unnecessary expectations that will take your body and mind out of “the moment.” Instead, take in the music, experience what is around you! Cherish the feelings and sounds instead of getting lost in a difficult passage coming up in the song. Often, we get so focused on what should be happening that we forget the beauty of being vulnerable. Noticing your music and your audience, and letting your body inhabit that space to move freely in it, is what will make for a memorable, moving performance.

When you practice, take your focus off how you are doing for a moment. Instead, focus on intention — why you play your music or what the writer/composer expresses through the piece you are playing. Then, focus on what you can do to embody that intention. Finally, experience the actions of your intention at the moment you perform it: breathing before a new passage, suddenly changing the dynamic, thrusting your fist in the air for a finale. The way to successfully embody your intention and physically express yourself is to allow your body to be alive. Live your music when you practice and perform. Everything else taking you out of the moment is clutter.

Great musicians are intuitive movers. The responsibility of our bodies while practicing is to “resonate” with our music. The reason for this resonance is so we may experience what we are doing as we do it. This is not exclusive to music; you may notice this mindfulness practice also pops up in religion, spiritual traditions, tai chi, and yoga. Presence and awareness are vital to understanding our physiology, mastering our focus while practicing, and living a more mindful life in general. We habitually limit our movements because of assumptions & misconceptions about how our bodies function. These mental and physical barriers influence how we use and think about our bodies every day, restricting our potential for musical expression. By bringing attention to how we move, we can understand what facilitates expression and what limits us.

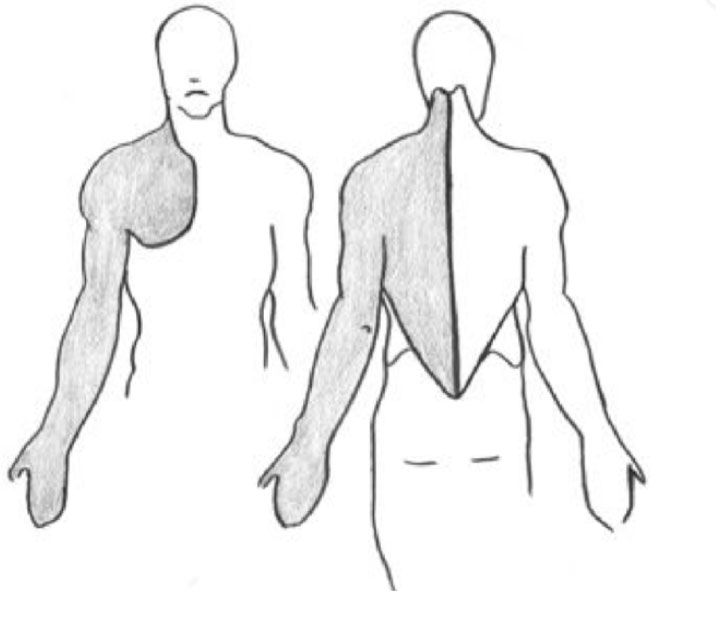

Notice how the muscles in your hand move as you play. For example, feel around your forearm as you wiggle your fingers. Feel any muscles moving? You might typically think the muscles that control your hand are only “in” your hand, but the muscles actually begin just above the elbow. The image shades all muscles and bones that keep your hands & arms moving during practice, all the parts of you that make up your “full arm.” Imagine having your hands at the piano or holding your guitar before a music lesson. Can you feel the muscles in your chest & back work together to move your arm? When you move in practice — whether you are practicing scales or a concert setlist — don’t isolate your attention to just your fingers, but notice your whole body as one connected form holding your posture.

Extending this awareness experiment to your torso muscles — as you move your head, arms, and legs — you would notice that all muscle groups that control your limbs overlap here. The convergence of muscle groups in your core supports all movement and is the foundation for expressing physical emotion.

There’s a zen saying that goes: “To become different from what we are, we must have some awareness of what we are.” What I am discussing in this article is a means to start your path to learning your body. This is not an immediate change, but it will incrementally make you more aware of yourself as you practice your music. With this new awareness, you will evaluate your body rather than flow through habit. Before there can be change, you must first calm & focus your mind. Don’t hurry. Make this unfamiliar process familiar, heighten your presence & free your body to move.

References:

Barker, S. (1991). The Alexander Technique: Learning to Use Your Body for Total Energy. Bantam Books.

Bond, M. (1993). Rolfing Movement Integration: A Self-Help Approach to Balancing the Body. Healing Arts Press.

Calais-Germain, B. (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Translated by Nicole Commarmond. Eastland Press.

Dychtwald, K. (1986). Bodymind. With a foreword by Marilyn Ferguson. Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Feldenkrais, M. (1972). Awareness through Movement. Harper and Row.

Gelb, M. (1981). Body Learning: An Introduction to the Alexander Technique. With a preface by Laura Huxley. Henry Holt and Company.

Jou, T. H. (1988). The Tao of Tai-Chi Chuan: Way to Rejuvenation. Edited by Shoshana Shapiro. Tai Chi Foundation.

Laban, R. (1971). The Mastery of Movement. Revised by Lisa Ullmann. Plays.

Schwiebert, J. (2012). Physical Expression and the Performing Artist. University of Michigan Press.

Solomon, E. P., & Davis, P. W. (1978). Understanding Human Anatomy and Physiology. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Snyder, C. (2017). Conducting 315: Instrumental Conducting. Ann Arbor; Kevreson Rehearsal Hall, Earl V. Moore Building, University of Michigan.

Todd, M. E. (1937). The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man. Princeton Book Company.